Canopy Atlanta asked over 50 Lakewood Heights community members about the journalism they needed. This story emerged from that feedback.

Canopy Atlanta also trains and pays community members, our Fellows, to learn reporting skills to better serve their community. Pristine Parr, a reporter on this story, is a Canopy Atlanta Fellow.

Checarda Lyons is a mother who’s lived in and out of Lakewood Heights since she was a teenager.

She is one of several residents who had observed that, following a community workshop held in March 2023, Policing Alternatives & Diversion Initiative (PAD) began leasing the old CHRIS 180 location, 1700 Lakewood Avenue, from the Society of St. Vincent de Paul Georgia (SVDP).

The ultimate vision for the building, led by SVDP, is to provide long-term housing. In the meantime, PAD is using 1700 Lakewood Ave. as a living room space to give clothing, hygiene items, and walk-in services for participants—and eventually, non-participants—who could use such resources. On Tuesdays, PAD also runs a weekly food pantry with Atlanta Community Food Bank, accessible to the entire neighborhood.

Today, Lyons sits with a group of locals, away from the sun under some old trees beyond the new PAD building, at the corner of Jonesboro Road and Lakewood Avenue.

“I was living in Augusta,” Lyons says, when she submitted her application for a Housing Choice Voucher, formerly known as a Section 8 voucher. After being on the waiting list for a little under six months, her voucher came through.

Lyons moved back to Atlanta while waiting. It cost her money that she didn’t have to get back to Augusta, and unfortunately, the voucher expired. If she’d gotten another voucher in Augusta, Lyons would’ve had to stay there for a year before it could be transferred to Atlanta.

Lyons says that a case worker eventually stopped taking her calls. So she returned to Lakewood Heights with no place to stay.

“A lot of us can’t pay what they charge in rent,” Lyons says. Even when there are a few housing options in Atlanta, inflated rent makes them affordable only to outsiders, forcing locals to move away.

And while this phenomenon is on par with a trend that social scientists say perpetuates racial and economic segregation in the United States, the trend feels especially hard to reconcile in Lakewood Heights. According to real estate company Point2, Lakewood Heights is dotted with over 2,200 unoccupied and rundown properties. That makes for a roughly 15 percent vacancy rate, compared to the city’s overall vacancy rate of 12 percent.

Barriers like what Lyons describes keep houses in visible states of decline, with both housed and unhoused community members scratching their heads about why those properties cannot be used to house families in need instead.

“It’s like now,” Lyons says, “that’s the only option you have if you even have a little bit of money . . . if you can, buy a property and try to make something out of it. But then, if you’re able to buy the property, maybe you’re not able to get any help that comes behind that.”

“Housing is worse now than it was back in the ‘80s, ‘90s,” Lyons says. When asked if she thinks it’s worse than it was 10 years ago, she says it’s “way worse.” She also estimates that local retail in Lakewood Heights has been shut down for at least the past 14 years, when her daughter was born.

Home construction rates in Lakewood Heights plummeted in the 1980s, when just 816 homes were constructed, which is less than half the number from the ‘70s according to Point2. Then in 1990, the General Motors plant—the area’s largest employer, with 5,700 workers at its peak—shut down after operating for 62 years.

“Over the years, early ‘90s, when people started to move out of the neighborhood, investors started buying up the properties,” Lakewood Heights developer Omar Ali previously told Canopy Atlanta.

Ahead of opening the retail center and event space Ali at Lakewood just a few blocks away, Ali surveyed every structure within a two-mile radius. What he found was a 67 percent vacancy rate, most of the vacancies being residential.

Ali said these investors, who own a significant number of both commercial and residential real estate in Lakewood Heights, have held onto properties without doing any renovations or taking other steps to make them ready to rent. Ali’s study of the area found that many homeowners had surviving family members who simply didn’t know how to go through the probate process.

The probate process in Georgia

If your deceased loved one’s estate needs to be probated in order for property to be deeded to a living family member, the Georgia Council of Probate Court Judges website provides standard forms for each step of the process. If in doubt, contact the Fulton County Probate Court via phone or in person to ask questions about the needed documents, filing fees, and timelines.

Another problem with individual or family-owned homes was backdated taxes that had not been paid by the previous owners.

“So we did a thorough interview with a lot of people, to where you may have the grandmother or grandfather who left the home to the grandkids with no will or anything, and they got tied up in probate court,” Ali said.

Today homeowners account for 36 percent of housing occupants in Lakewood Heights, compared to the City of Atlanta’s 45 percent owner-occupied housing unit rate.

As Lakewood Heights residents see the neighborhood suffer, there’s an underlying skepticism toward people who do not live in the community who hold onto abandoned properties. Lyons says a lot of white people, especially, own properties that they are not even trying to fix up.

“But then,” she added, “you got people out here who really need somewhere to be.”

Early one August morning at Community Grounds, the coffee shop just one mile north of PAD’s new community center, Rick Sakaske meets with two colleagues for their daily get-together. All three have extensive backgrounds in community work. Their practical support of each other and Lakewood Heights residents gives them a quirky, youthful energy, even though the group members’ average age is over 70 years old.

Sakaske is a veteran volunteer who assisted unhoused people for over a decade. He worked at the foot clinic at Central Presbyterian Church for 15 years, and his wife, Helen, used to coordinate meals at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception’s night shelter.

For several of the nine years that Sakaske has lived in Historic South Atlanta, he offered daily assistance to his fellow community members like Reginald, who lost his home in a fire and moved inside another, dilapidated house. After the original homeowner died, “his wife went to a home or something,” Sakaske says. And so Reginald moved in “just to take care of the place.”

“[Reginald] lived in a house that didn’t have water for seven years,” Sakaske says. “Two miles away from downtown, seven years, didn’t have water. The man used to pay a neighbor to take a shower once a week.” Sakaske also brought Reginald buckets of water so he could flush the toilet and wash his hands.

When the homeowner’s wife died, “the uncle took over, and he stayed in the place. Then the uncle died, and the niece finally got it,” Sakaske says.

Once the homeowner’s niece took over and decided to sell the house, Reginald had to leave. Sakaske helped Reginald relocate to a 55-and-over community on Springdale Road and currently pays his rent.

For Lyons, sleeping outside isn’t exactly a choice, when she doesn’t have a place to go.

“They closed all the shelters,” she says, explaining how shelter closures have affected primarily women and children, and how the whole community benefits when women and children get the resources they need. “[Women are] the ones that make the children stable, that make them stronger and can help a man be a better man,” she says.

Lyons was among a number of women we talked to who thought that PAD and other direct-services providers help only men. Though false, there are fewer options for live-in recovery and emergency housing for women in Atlanta overall. But what Lyons says about shelters is correct—the number of beds in Atlanta has declined dramatically in recent years, mainly because of the closure of the Peachtree-Pine shelter in 2017.

Nearby shelters for unhoused residents

Gateway, about four miles away from Lakewood Heights in downtown Atlanta, provides cold-weather shelter and associated services, though is often full. Gateway also provides housing for women through the Trinity Women’s Center. Everyone must complete coordinated entry forms to receive services.

The Salvation Army Atlanta Red Shield Services Emergency and Transitional Housing Facility on Marietta Street is likely the best walk-in option. Anyone can check themselves in and those with an income may be charged $10 per night.

Atlanta Mission: The Shepherd’s Inn is another option for men in need of shelter, a hot meal, or counseling. The mission’s other facility, My Sister’s House off Howell Mill Road, provides overnight shelter and services for sober women and children on a first-come, first-served basis.

Nicole’s House of Hope on M.L.K. Jr. Drive in west Atlanta is accessible by MARTA and provides transitional housing and permanent housing options.

Specific to Lakewood, the Villages at Carver is an income-based apartment solution, with rent for a 750-square-foot apartment with one bedroom and one bathroom hovering just below the city’s median rent of $1,512, according to the U.S. Census. A little more affordable than that, a mixed-income complex called Haven opened where Chosewood Park meets Lakewood Heights earlier this year, with one-bedroom units ranging from $1,051 to $1,250. While these are certainly options for some, the cost may be insurmountable for others who are unemployed or living on a fixed Social Security income.

Additionally, convictions for certain offenses, outstanding court fines and fees, and multiple arrests can prevent people from getting into a home. Though fewer than .5 percent of all Atlantans experienced homelessness in 2022, 12.5 percent of those incarcerated at Atlanta City Detention Center did.

In May 2023, Atlanta police made 128 diversion-eligible arrests in Zone 3, which includes Lakewood Heights and a few surrounding Southeast Atlanta neighborhoods—more than any other police zone. Like all arrests of people living on the streets, the two most cited offenses in Zone 3 were criminal trespassing and panhandling. Basically, people are increasingly being arrested for having nowhere to go and trying to survive.

Perhaps Lakewood residents know that this practice of criminalizing a person because they’re poor is often the very thing that prevents that person from getting housing.

“Everything is intertwined,” Lyons says. “Everything all go together. The whole Lakewood Heights—everybody always in Fulton County Jail.”

Like all arrests of people living on the streets, the two most cited offenses in Zone 3 were criminal trespassing and panhandling. Basically, people are increasingly being arrested for having nowhere to go and trying to survive.

Even with government programs, someone who needs housing the most ends up “not the person they want to give it to,” Lyons says. One paradox that unhoused folks face is that many housing applications require a current or previous address. It’s easier to get into housing when you already have housing.

The barriers people face by having been criminalized are also exacerbated: There is a significant overlap of unhoused people and people with conviction histories. On top of the lawful discrimination and stigmas that come with criminalization, 41 percent of those who experienced homelessness in Atlanta in 2022 had unpaid court fines and fees and are still expected to pay them.

With renting, barriers usually have to do with whether the person has been arrested at some point, despite the fact that Atlanta City Council passed an ordinance to make formerly incarcerated people a protected class against this very discrimination last year.

“That’s what has a lot of people stuck in a situation,” Lyons says, “even people who do pay actual rent.”

As a homeowner, Sakaske sees the same thing. “There’s all different issues. And it’s something that you’re not going to solve like that,” he says, snapping his fingers. “It needs to be monitored. Like the guy down here, he’d been shot in the face [years earlier]. Been down here forever. Just got killed, run over . . . three months ago, he was in a wheelchair, seven o’clock at night.”

Sakaske remembers another South Atlanta resident who he believes struggled with mental illness before she passed. He said that police officers and community members saw her all the time but nobody did anything to help her.

“Everybody not understanding—there’s no control,” Lyons says. “Because people are not able to control themselves. So with that aspect, Lakewood Heights has a lot of . . . people with mental issues. And unchecked.” But these same residents cannot access care to address such issues, Lyons says.

“We had clinics back when I was a teenager and a new adult,” Lyons says. Local clinics, including the now-condemned Lakewood Health Center on Jonesboro Road, filled the gap where hospitals and doctor offices were missing. “All the clinics we had right here in this general community, from here to Carver High School—they’re gone.”

As a volunteer at SVDP, Sakaske helps shape South Atlanta into a better place, one person at a time, one event at a time.

“That’s all we try to do, all of us. Make somebody smile today. Leave a footprint here. We’re not turning the world around . . . But eventually, most people tend to say, ‘You know what, it’s time to help people. There’s more to life than just me.’”

Sakaske says that he’s put himself in unsafe situations when trying to assist unhoused residents in the past. He also wonders whether what he and his colleagues do for their fellow community members is enough.

“All we do is put a Band-Aid on it,” he says.

As far as non-governmental solutions, PAD is known for providing individualized care. Based on a data-driven national model for neighborhood response that connects people to wraparound services rather than incarceration, PAD provides pre-arrest options.

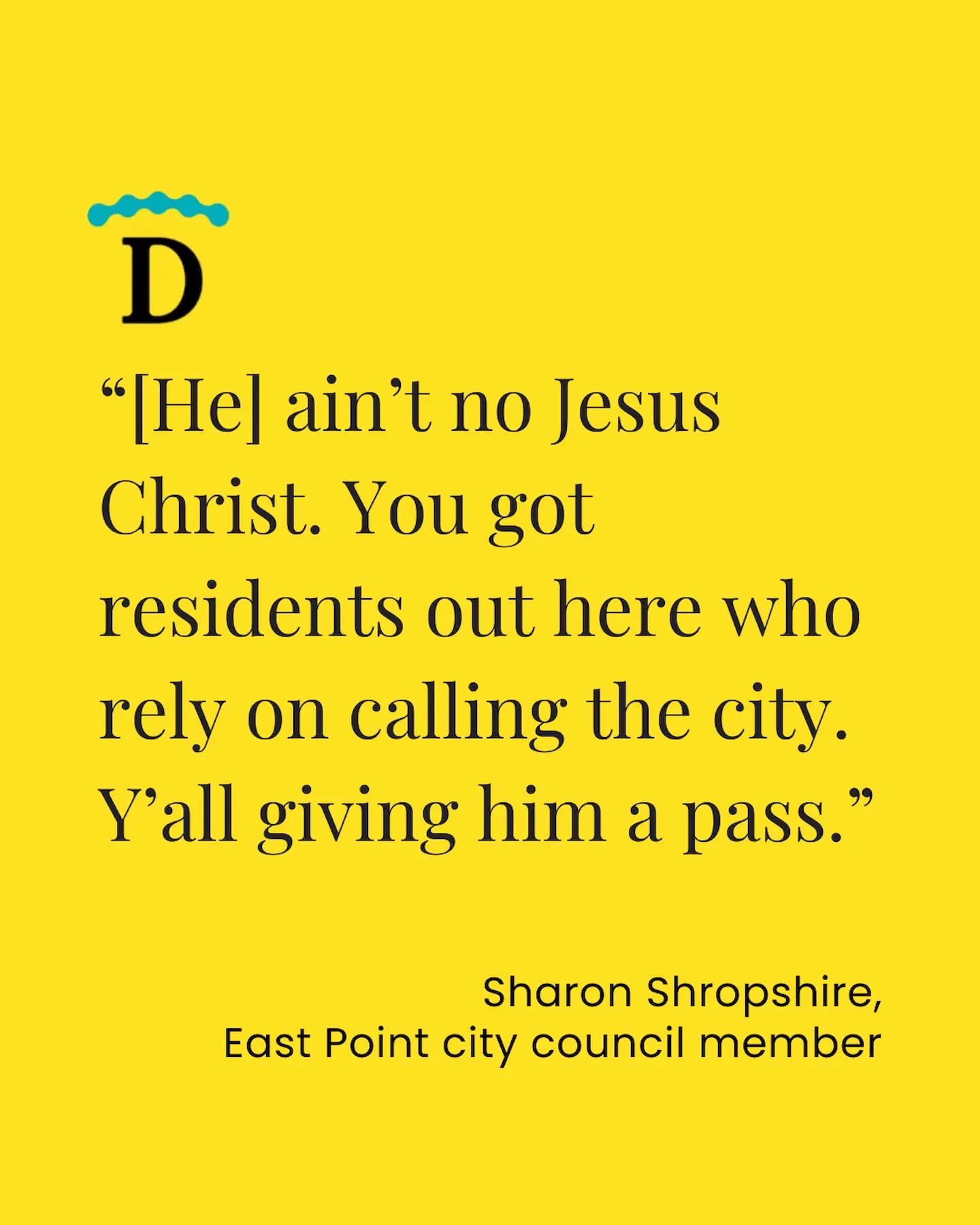

“When folks in the community are seeing other community members who are experiencing quality-of-life concerns, whether it’s mental health concerns, or especially, homelessness, they can call 311,” explains Julianna Johnson, PAD’s housing manager. Residents in all neighborhoods of Atlanta are encouraged to call 311 instead of calling the police when they see someone dealing with quality-of-life issues.

Who to call to assist an unhoused resident

While directing people to the PAD building for immediate resources is an option, calling 311 should still be the go-to. But what happens when you call?

“First,” PAD’s housing manager Julianna Johnson says, “our community response team is going to go out and meet the person where they’re at, engage them, assess the situation, and ultimately, connect them to a care navigator who is going to help them reach their goals long-term.” One thing PAD is known for is keeping community members informed, which means following up with callers so they know the outcomes of their referrals.

Grady EMS responds to 911 calls that specifically request mental health triage. And for mental health situations that don’t present an immediate physical health risk, Atlanta residents can call the Georgia Crisis and Access Line at 800-715-4225.

But as of December 2023, PAD is helping 279 actively enrolled participants. To put that into perspective, the Atlanta Community Support Project counted over 2,600 folks who experienced homelessness in Atlanta just in 2021 and 2022. The need is drastically bigger than the available funding: The city’s public safety budget pays for things other than critical public safety resources, such as jail maintenance, Atlanta Police Department operations, and public safety technology.

“What this community really would need from the city, in my opinion, is a social worker,” Sakaske says. One who could visit the neighborhood once a month and support people in need of food, shelter, or other resources based on their individual needs. If one such social worker exists, Sakaske isn’t aware of them.

Unhoused residents “need somebody to guide them, to give them some direction,” Sakaske says. In his opinion, that’s where the city should step in.

On the other hand, Lyons says she knows exactly what she needs to move forward. It’s just that, while coordinating with a social worker, she ended up unhoused anyway.

Returning to Lakewood Heights, however, has Lyons convinced that the heart of the neighborhood remains intact.

“I love Lakewood,” Lyons said, “even with all the problems it’s got.”

As Lyons and I chatted under the old trees near PAD, we saw visible support actively happening around us—people bringing each other lunch and dropping off groceries; mutual aid, really. The scene affirmed Lyons’s words.

“No matter what we got going on, we stick together. This is our neighborhood. The spirit of community lives here.”

Editor: Christina Lee

Copy Editor & Fact Checker: Adjoa D. Danso

Canopy Atlanta Reader: Kamille Whittaker