Canopy Atlanta asked over 140 Tri-Cities community members about the journalism they needed.

Residents raised the area’s walkability and existing public transportation as major issues. One East Point transplant said the area isn’t a safe place to walk—“which, if fixed, can enhance the sense of community.”

Canopy Atlanta also trains and pays community members, our Fellows, to learn reporting skills to better serve their community. Faith Mbadugha, a reporter on this story, is a Canopy Atlanta Fellow.

When Kyle Stanton worked at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport in 2023, he was only a mile away from work. But he would have had to leave two hours early to use public transit, so he drove.

The ability to bypass traffic and travel without a car on a path that provides shade and feels safe would be huge for Tri-Cities residents. For those working early or late shifts at the airport, or those trying to travel across College Park, East Point, and Hapeville, walkability and public transportation can be a struggle.

Multi-use trail investment has been “north of I-20, it’s been in the northern suburbs, it’s been the Beltline,” says Josh Phillipson, a transportation specialist at the Atlanta Regional Commission. “Not that it hasn’t gone through neighborhoods that really needed it, but there’s a gap on the map in the area that we’re looking at here.”

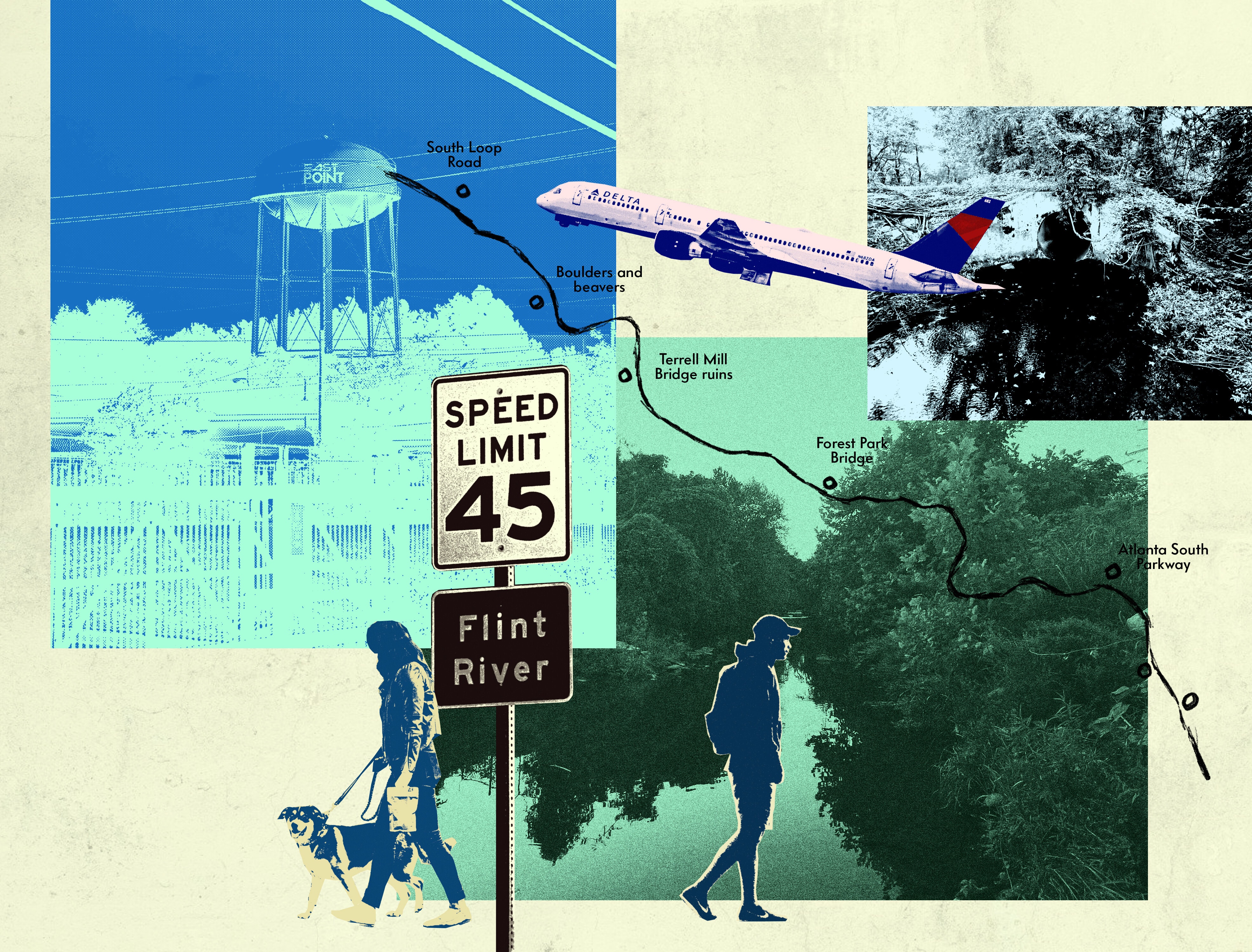

Residents may not realize that the mighty Flint River (in fact, Georgia’s second longest) starts near a water tower in East Point and flows beneath and beyond the airport runways, joining the Chattahoochee River and reaching Lake Seminole in Southwest Georgia.

Following the Flint River south would provide more direct connectivity through the Tri-Cities.

“It’s just currently off-limits,” says Hannah Palmer, an author and urban designer. “The river follows a really logical course downstream. If we just follow the water, if we act like raindrops, it gets us to our destination faster.”

Palmer helped secure $65 million in federal funding for the Flint River Gateway Trails, a 31-mile trail network that would link southwest Atlanta to the Atlanta Beltline, loop around Hartsfield-Jackson, and follow the Flint River south. The trails would connect the Tri-Cities by tracing through the river that flows through them all.

Through the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, the U.S. Department of Transportation awarded the ARC, Clayton County, and the cities of College Park, East Point, and Hapeville a grant from funds earmarked to invest in areas negatively impacted by infrastructure like major highways.

The grant application included more than 50 letters of support from community groups and nonprofits, including Tri-Cities arts organizations ArtsXchange and Ballethnic Dance Company, and Senator Raphael Warnock. The application built upon the findings of a dozen studies for walkability and multi-use trails in the region.

“This is a singular opportunity where there’s significant money going through this program,” Phillipson says. “How can we make those connections where they’re most needed?”

For hundreds of years before the airport, paved roads, and county lines existed in the Tri-Cities, the Flint River drew people to the region.

In the 1800s, the U.S. government sold much of the land around the Flint River as farm land. The river made nearby land fertile, spurring fruit and cotton farms, and it served as a means of transporting goods.

In the early 1900s, following the invention of the streetcar, the Tri-Cities transformed into distinct urban centers with their own “Dummy Train.”

“In the very early days of Hapeville, it was considered a hotspot for wealthy Atlanta families to come down here and vacation because the water was so good,” says Samantha Singleton, manager of the Hapeville Depot Museum.

Today, the Tri-Cities lack the connectivity once provided by the streetcar and railroad networks. In the 1960s, transportation and industrial development initiatives revolving around Hartsfield-Jackson took land from Hapeville, East Point, and College Park to build highway infrastructure.

“They’re talking about these runways being built and [Interstate] 85 getting pushed in through the neighborhood,” Palmer says. “I-285 [was built] right on top of neighborhoods. There was a really existential threat to these cities because of the growth of Atlanta’s airport.”

While the airport and its infrastructure have increased the ease of transit across the nation and the world, it’s wiped entire cities off the map in southwest Atlanta (like Mountain View, much of which was acquired by the city through eminent domain to make way for the airport). Airport construction also restricted the mobility of residents and left the Tri-Cities to years of disinvestment for the lower-income Black communities that remained.

As a result, the Southside has experienced the slowest growth in metro Atlanta since the 1990s, even as the airport has expanded, and faces some of the highest rates of poverty and cost-burdened households in the region.

College Park native Noel Mayeske had family members who worked for Delta. He remembers growing up in a neighborhood with fancy parties and an elite, “nearly exclusively white” population. Mayeske can trace white flight from the area through the changing makeup of his classmates at S.L. Lewis Elementary in the 1970s following the integration of Atlanta schools.

“It flipped totally just based on the racial prejudices pretty much of white folks like me,” he says. “White flight, based on racism, changed the demographics and the whole face of College Park.”

Today, less than 15 percent of the Tri-Cities population is white. The communities around the airport rank last in the metro for acreage of park space per capita, and residents face some of the worst air quality in the nation, according to the grant application for the trails project.

Palmer grew up in Clayton County, but she didn’t explore the Flint River until she was living in East Point as an adult.

Since then, Palmer has given over 60 tours of the river with stakeholders and community members. She also wrote a book, Flight Path: A Search for Roots Beneath the World’s Busiest Airport, about the airport’s impact on South Atlanta.

Palmer’s tours trace the Flint River’s flow along busy roadways, through a hotel parking lot storm drain, down a culvert beside the Delta Flight Museum, and beneath the looping highway that provides access to Hartsfield-Jackson, adjacent to hundreds of private properties. The tour path follows public roads, but most of the river corridor is on private property and behind security fences.

Delta’s campus sits on a section of the river leased out by the City of Atlanta Department of Aviation. Currently, the water is hemmed in by a concrete channel.

A tour in August included evidence of beavers and raccoons, and sightings of about a dozen deer and a rare winged elm tree. Meanwhile, the proximity to the airport raises the risk of pollution from jet fuel and other runway runoff from dirtying the river water.

In 2017, the Conservation Fund, based in Arlington, Virginia, in partnership with American Rivers and the Atlanta Regional Commission, hired Palmer and Atlanta Beltline designer Ryan Gravel to brainstorm what it might look like to restore the river, connect greenspace around the airport, and bring access and life back to the community, says Stacy Funderburke, who oversees the fund’s land conservation efforts in Georgia and Alabama.

The ultimate goal of the initiative, Finding the Flint, is to restore the river to its original course. Starting at the beginning of the river in East Point, the restoration team will remove fences and pavement and then create public parks that will be connected by walking and biking trails.

The Conservation Fund worked for over two years to help the city of College Park gain ownership of land from MARTA: seven acres around the headwaters where East Point and College Park intersect.

Four years ago, the Conservation Fund also acquired 12 acres along Mud Creek, the Flint River tributary most affected by airport pollution. Clayton County plans to restore the land along the waterway.

The U.S. DOT grant is meant to cover 3.3 miles of construction for multi-use trails, the scoping and engineering for 10.5 more miles of multi-use trails, and stormwater management of the Flint River Gateway Trails. “This gives us a chance to try to push all these things forward at the same time, which is really exciting,” Funderburke says.

But the ARC won’t be able to start spending the federal grant until early 2025 since the money is expected to be awarded in the fourth quarter of this year, Shannon James, president and CEO of the Aerotropolis Atlanta Alliance, says.

And more investment from other sources will be required to execute on the larger vision. ARC and Aerotropolis Atlanta are working with Clayton County and the Tri-Cities governments to secure additional funding from the state of Georgia and philanthropic sources.

No single county or government is in charge of managing and maintaining the river. That’s why the ARC took a lead role for the federal grant, with Clayton County, College Park, East Point, and Hapeville all acting as project partners.

“This is a chance to really look at the hardest connections to make. These are multi-jurisdictional. This [federal grant] isn’t something that East Point could apply for by itself, or College Park,” Phillipson says. “This is something that had to be done as a partnership.”

Palmer wants to see more engagement from the City of Atlanta.

“We’ve gotten some support from the airport, which is a City of Atlanta department,” Palmer says. “They’re tolerating me. Their sustainability team has been key—letting us do clean-ups on site, education on-site. But actually putting in any money—that hasn’t happened yet. I think their participation is going to be really important as these trails get into design and construction near the airport.”

(The mayor’s office didn’t respond to Canopy Atlanta’s request for comment.)

Renderings of the proposed Flint River trail network. Provided by Finding the Flint.

Palmer believes that the airport could do more to help mitigate flooding and runoff by prioritizing green management of its 4,700-acre footprint. There are areas along the early flow of the river where more vegetation, rather than additional man-made barriers, would help prevent erosion and improve the water quality.

“The airport isn’t the only culprit, but it is part of the solution,” Palmer says. “Better stormwater management at the airport would make a big difference downstream.”

However, there’s a “tense relationship” between the city and Clayton County Water Authority, Palmer says. The impacts of the airport and its infrastructure—both in water quality and flooding risks—are borne and paid for largely by Clayton County residents.

Experts and leaders from the ARC and Aerotropolis Atlanta say that while this trails project is just getting started, they are listening and learning.

“We’re working on exactly what that public involvement will look like. It’s a really important part of all of this work that this is putting the residents at the center,” Phillipson says. In close collaboration with Aerotropolis Atlanta, the Conservation Fund, and others, “we’ll do specific engagement with folks who live along or work along the trail alignment as well.”

James hopes that the trails project will bring the area more commercial and residential real estate investment and create jobs after decades of being under-resourced.

He’ll also look to the Beltline’s example to see that longtime residents enjoy those benefits. “The Beltline has been pretty honest about the growth that has happened that they could control and that they couldn’t control,” he says. “They were smart about creating an entity that could now acquire real estate so that they could then control what goes vertical. Those are things we’re thinking about, too.”

James says that making sure that the project doesn’t displace legacy residents keeps him up at night: “It’s like a double-edged sword.” He encourages residents to follow Aerotropolis Atlanta and sign up for the Aero Insider newsletter to stay up-to-date on the project and opportunities to provide input and feedback.

“Whenever you make an improvement in a community that is growing, you make it more desirable, and therefore potentially drive up values that translate into rents and home prices,” Gravel, the urban designer who created the initial idea for the Beltline, says.

“It’s only really a problem if local jurisdictions don’t have protections in place for people,” like housing affordability policies or economic opportunities, he adds.

Everyone seems in agreement that investment into repairing the river and improving quality of life for Tri-Cities residents is long overdue.

Mayeske’s hope is that the Flint River project will change perceptions of College Park. He feels perceptions are currently centered around crimes that make the news.

Stanton, now a historian at the Hapeville Depot Museum, hopes the trails will bring more tours of the river, and more interest in the towns that are no longer around to see the river’s revitalization.

“I think work would probably need to be done explaining the individual communities, why they exist, who lived there before,” he says. “I think there can be a positive community identity. But, yeah, it’s difficult when the Atlanta airport’s right there. People are just driving past, and they might never know there’s communities there, really.”

Editor: Christina Lee

Fact Checker: Adjoa D. Danso

Canopy Atlanta Reader: Genia Billingsley

I hope this story leaves you inspired by the power of community-focused journalism. Here at Canopy Atlanta, we’re driven by a unique mission: to uncover and amplify the voices and stories that often go unheard in traditional newsrooms.

Our nonprofit model allows us to prioritize meaningful journalism that truly serves the needs of our community. We’re dedicated to providing you with insightful, thought-provoking stories that shed light on the issues and stories that matter most to neighborhoods across Atlanta.

By supporting our newsroom, you’re not just supporting journalism – you’re investing in Atlanta. Small and large donations enable us to continue our vital work of uncovering stories in underrepresented communities, stories that deserve to be told and heard.

From Bankhead to South DeKalb to Norcross, I believe in the power of our journalism and the impact it can have on our city.

If you can, please consider supporting us with a small gift today. Your support is vital to continuing our mission.

Floyd Hall, co-founder