Canopy Atlanta spent summer 2024 surveying residents living in some of the lowest voting precincts in metro Atlanta. After analyzing the Secretary of State's data on these precincts, we had questions, so we sent an Atlanta Civic Circle Democracy reporter on a quest to dig beyond the data. Here’s a story about what he found.

Even though Georgia posted record voter turnout numbers statewide for its presidential and midterm elections in 2020 and 2022, voter turnout remained low in predominantly Black and lower-income communities in the south and west of Atlanta’s metro area.

These precincts have some of the lowest voter turnout percentages in the 5-county metro Atlanta area, many of which have less than 50 percent registered voter turnout, according to precinct data analyzed by Canopy Atlanta and a separate analysis by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

But what’s behind the disparity?

Factors such as income, age and race are indicative of lower turnout, with younger, lower-income and non-white voters typically voting at lower rates. Atlanta Civic Circle and Canopy Atlanta have also previously reported that redistricting — how the boundaries of state senate and state house districts are drawn – may be a factor.

But that’s not all. Data experts say the voter turnout numbers are more complicated than even all of those factors combined. In neighborhoods with more transient populations, such as students, rentors, or areas with significant gentrification, the voter rolls may not accurately reflect how many voters are living in any given precinct. If a voter doesn’t notify the state of a move, the date may “lag” behind for up to eight years before it is updated.

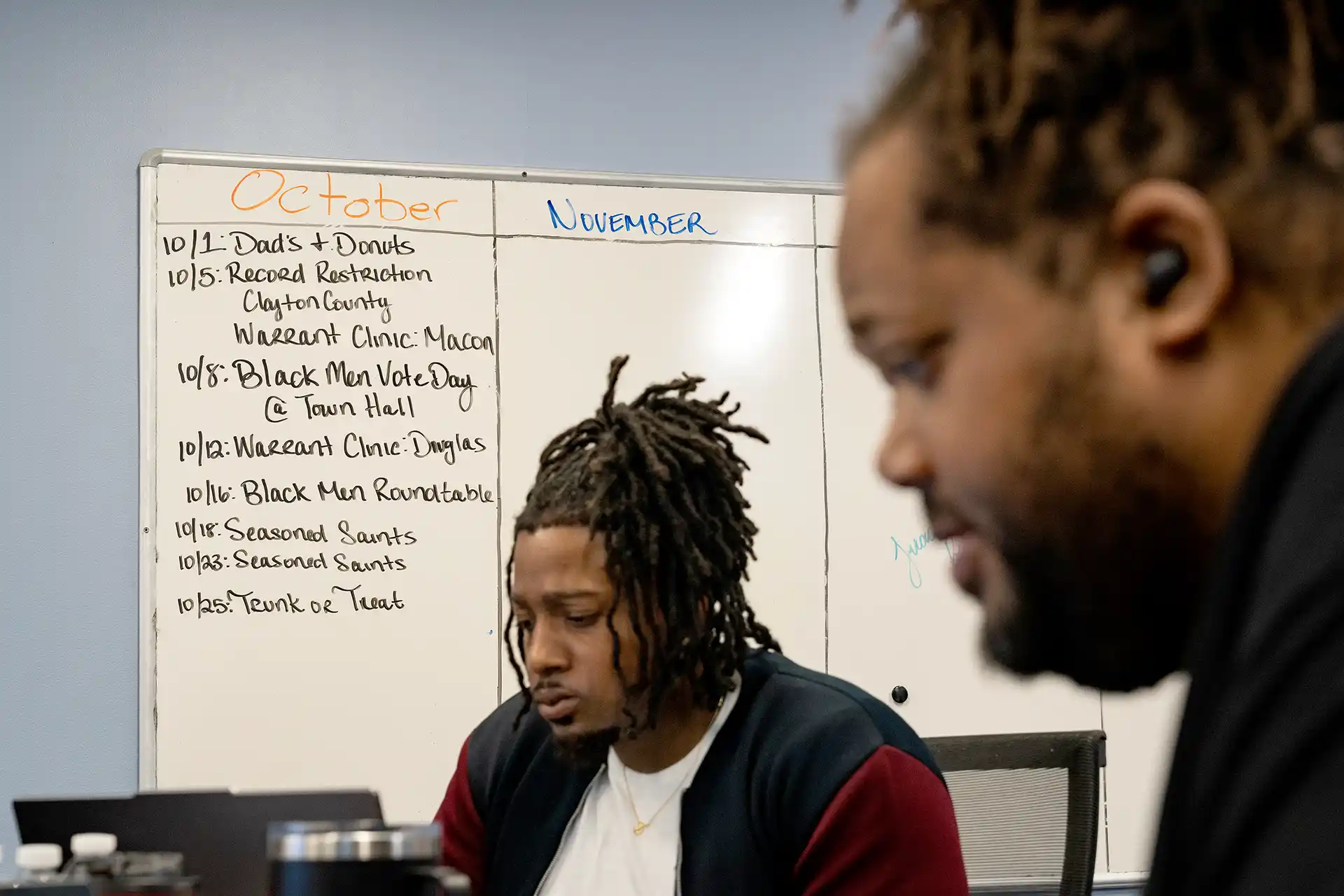

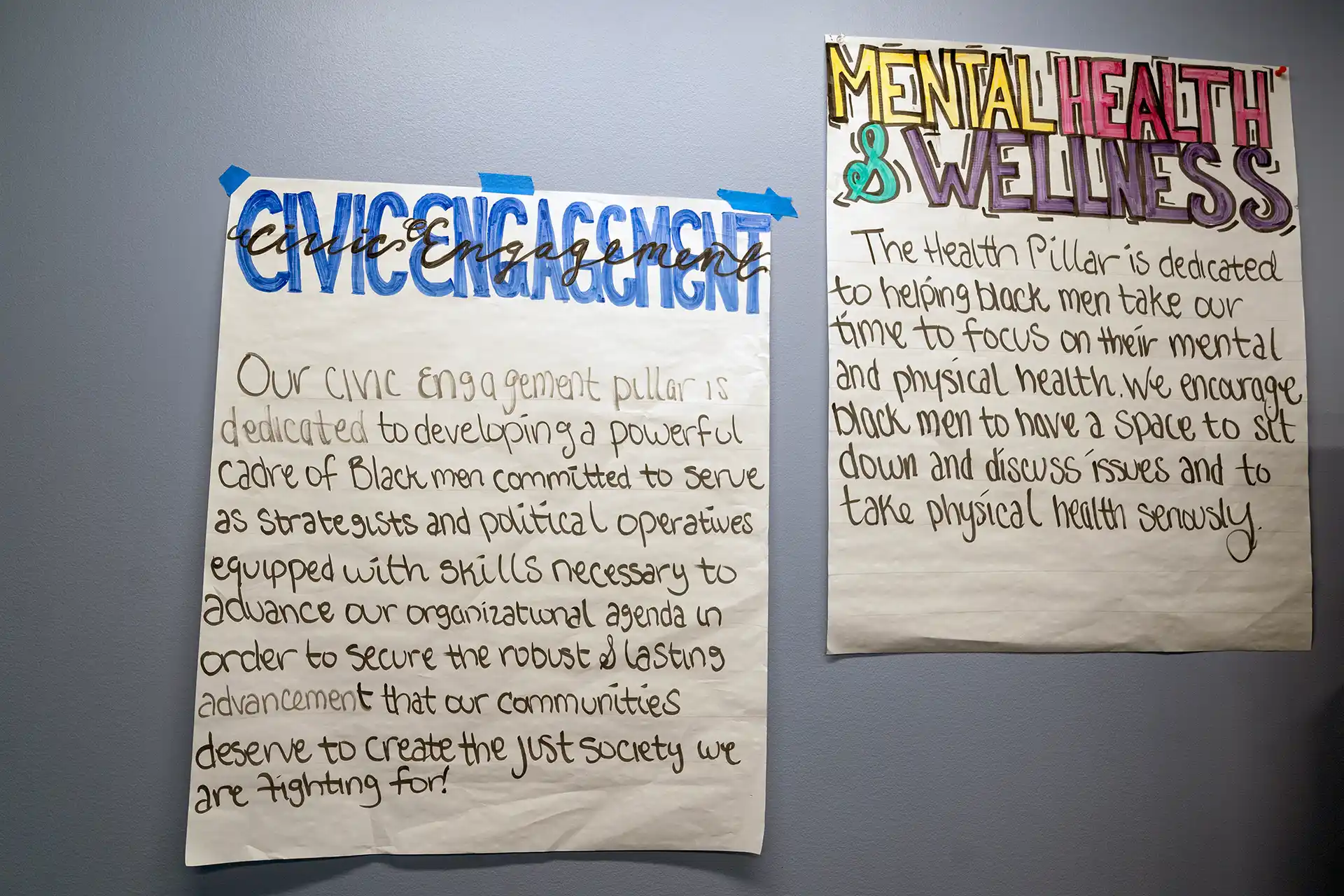

John Taylor, executive director of the Black Male Initiative, an organization dedicated to empowering Black men through civic engagement and grassroots organizing, noted all of these factors.

“Sometimes the depressed voter turnout is a representation of people traveling, moving,” he said. “I absolutely, in no way, shape or form, would blame the voters [for low turnout].

“We know it takes years to cultivate a voting base, a residential and civic base inside of communities that don’t even have their own police, fire, water infrastructure… where they’re still using some infrastructure support from the city of Atlanta proper,” he said.

“I absolutely, in no way, shape or form, would blame the voters [for low turnout],” Taylor said.

Taylor noted that many of the areas in south Fulton County are going through processes of redevelopment and gentrification where there are also still transient populations and labor forces such as those working in the airline industry.

“Whether it’s the lack of resources allocated to mobilize our base communities, the intrinsic and compounding hurdles and oppressive dynamics that we face… the process is getting harder, less inviting and less engaging,” Taylor said, pointing to laws such as S.B. 202 that critics say depress voting access.

Senate Bill 202, passed in 2021, enacted a series of provisions its proponents say tighten election security but that the ACLU has alleged unduly burden and disenfranchise Georgians with disabilities. However, elections since its passage have seen increased voter turnout.

Kyle Kessler, policy and research director at the Center for Civic Innovation (CCI), a community engagement think tank, said there hasn’t been enough of a “typical” election to draw any firm conclusions about whether SB 202 has impacted turnout.

“There’s lots of other motivating factors about who’s on the ballot and how they’re going to drive folks to want to engage or not,” he said, adding that “I don’t know of anything super definitive that said it has explicitly had this effect. I think there were some well-founded fears.”

Understanding voter registration and turnout

Voter turnout is the rate at which registered voters exercise their right to vote in a given election. This is usually measured as the percentage of registered voters that cast a ballot on a given year.

Voter registration rates measure how many people are registered to vote out of the total voting-eligible population of citizens of voting age without legal restrictions on their rights (such as someone currently serving a felony conviction).

In Georgia, The Secretary of State’s Office, which is responsible for election administration, routinely “cleans” voter rolls — the list of active registered voters in the state. In the past year, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger has overseen the cancellation of nearly 190,000 voter registrations for a variety of reasons such as deceased individuals, felony convictions or people moving out of state. Voters who have not voted for eight years (or two presidential general elections) are also subject to having their registration canceled due to “inactivity”.

Keeping voter rolls up to date is necessary and helps maintain confidence in elections but rights groups such as the ACLU and NAACP have raised concerns about errors in the process, and that lower-income voters of color are disproportionately affected.

Voters whose voter registration are nearing cancellation are supposed to be notified. Still, it’s easy for those mailers to get lost, or be ignored because it “may look like junk mail,” said Taylor.

“If I was purged from the voting rolls and nobody notified me, or they say they tried to notify me, but there was never a real conversation […] and I show up on election day to where I’m supposed to vote, where I think I’m supposed to vote, and I’m being told: now you have to do a provisional ballot [ …] that’s rough on Election Day,” he said.

Taylor agreed that the Secretary of State’s maintenance of voter rolls is such that there is little concern that turnout data is skewed because of excess of inactive or ineligible voters lingering on the lists.

RELATED: Where has all the info gone?

For the Nov. 5 General Election, voter registration closed on Monday, Oct. 7. That means the list of people registered to vote by that date is locked in by law, and their right to vote in the upcoming election is guaranteed. You can check your voter registration status in Georgia on the Secretary of State’s My Voter Page.

Unpacking the data

Speaking to Atlanta Civic Circle and Canopy Atlanta for this story, Secretary of State spokesman Mike Hassinger expressed confidence that Georgia’s voter registration lists are as accurate as possible.

“We use every available legal method to ensure that every voter on our rolls in Georgia is who they say they are, they’re an American citizen and that they’re legally entitled to vote,” he said, noting that the only limiting factors are the “lags” of a real life voter being slow to notify a name change or a change of address.

“It’s not a static database. It’s being monitored and kept up with by 159 counties at the county level every day. We can’t change a voter’s name without the voter telling us that they’ve gotten married and changed their name. We can’t update their address without the voter contacting us and telling us that they’ve got a new address. So we lag behind real life but that doesn’t mean that our numbers aren’t accurate.”

The Secretary of State’s office also uses tools such as the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC), the United States Postal Service National Change of Address database (USPS NCOA), the Vital Records Bureau, obituaries, reports from family members, the Georgia Crime Information Center, and jury lists reported by Clerks of Court to ensure accurate voter lists, conforming with accepted best practices.

Kessler with CCI agreed that the Secretary of State is generally following best practices and that the use of voter registration maintenance tools “helps keep us with a fairly fresh and accurate accounting.”

Even concerns about voter purges, Kessler said, “are a little bit blown out of proportion” although that is “not to say there are not Republican and far right-wing efforts to do a lot of likely excess purging.”

“I don’t want to give our Secretary of State too much credit, but I think he’s doing a pretty good job in the institutions and policies that they have, I think they are pretty good in a non-partisan, bipartisan sort of fashion,” he said.

Tommy Pearce, executive director of Neighborhood Nexus, a regional information system, noted that what is hard to figure out more than turnout rate, is registration rate, because it is difficult to determine what the number of eligible voting age adults is at a given time.

“Understanding who’s 18 and older and eligible to vote, that’s a tough number to come up with… My guess is that the percentage of voting age adults that actually are not eligible to vote is higher than we think,” he said.

When it comes to turnout and raw registration numbers, Pearce says that they rely on the Secretary of State’s data, and consider it to be reliable.

Rapidly changing areas

The low turnout precincts identified by Canopy Atlanta, situated predominantly in the western side of Atlanta and the south of Fulton county are rapidly changing areas of the city. Structural barriers that lower-income voters of color may face are also compounded by gentrification and development that can disrupt a community, voting advocates say.

“I mean, I’m looking at working-class, Black neighborhoods, but then I’m also looking at transitioning gentrifying neighborhoods like Castleberry Hill and in and around the Mercedes-Benz stadium,” said Nsé Ufot, a community organizer and former chief executive of the New Georgia Project. “I think these places are where transplants and people new to Atlanta come as a first place.”

Kessler, with CCI, pointed out that some of those precincts are located near several Atlanta universities, and another — which happens to be Kessler’s precinct — downtown on Trinity Avenue is located next to a transitional center. These “high churn” areas he said are likely to produce statistical outliers.

Residents in those situations may not update their address or registration information within the years-long period it would otherwise take them to be removed from the rolls for inactivity, or otherwise trip one of the mechanisms the Secretary of State relies on, Kessler said.

“I can understand why there might be a lagging sort of factor in getting some of that information up to date,” he said.

Editor: Stephanie Toone

Copy Editor & Fact Checker: Julianna Bragg

Canopy Atlanta Reader: Mariann Martin

I hope this story leaves you inspired by the power of community-focused journalism. Here at Canopy Atlanta, we're driven by a unique mission: to uncover and amplify the voices and stories that often go unheard in traditional newsrooms.

Our nonprofit model allows us to prioritize meaningful journalism that truly serves the needs of our community. We're dedicated to providing you with insightful, thought-provoking stories that shed light on the issues and stories that matter most to neighborhoods across Atlanta.

By supporting our newsroom, you're not just supporting journalism – you're investing in Atlanta. Small and large donations enable us to continue our vital work of uncovering stories in underrepresented communities, stories that deserve to be told and heard.

From Bankhead to South DeKalb to Norcross, I believe in the power of our journalism and the impact it can have on our city.

If you can, please consider supporting us with a small gift today. Your support is vital to continuing our mission.

Floyd Hall, co-founder