Canopy Atlanta asked over 90 Collier Heights community members about the storytelling they needed in their community. In those conversations, neighbors expressed concerns about the changes happening. “There are a lot of rental properties that are coming up. There are a lot of investors coming in that are not abiding by the historic regulations,” one person said. Another shared, “Myself and the historic preservation committee—we work every day to work against investors, keep the architectural design.” This story emerged from what we heard from community members.

Canopy Atlanta also trains and pays community members, our Fellows, to learn reporting skills to better serve their community. Akua Taylor, the reporter on this story, is a Canopy Atlanta Fellow.

Collier Heights has not gentrified…yet.

That sentence settles in your chest like something between a warning and a promise. Depends on who’s saying it. Depends on who’s listening.

``Collier Heights has not gentrified...yet.``

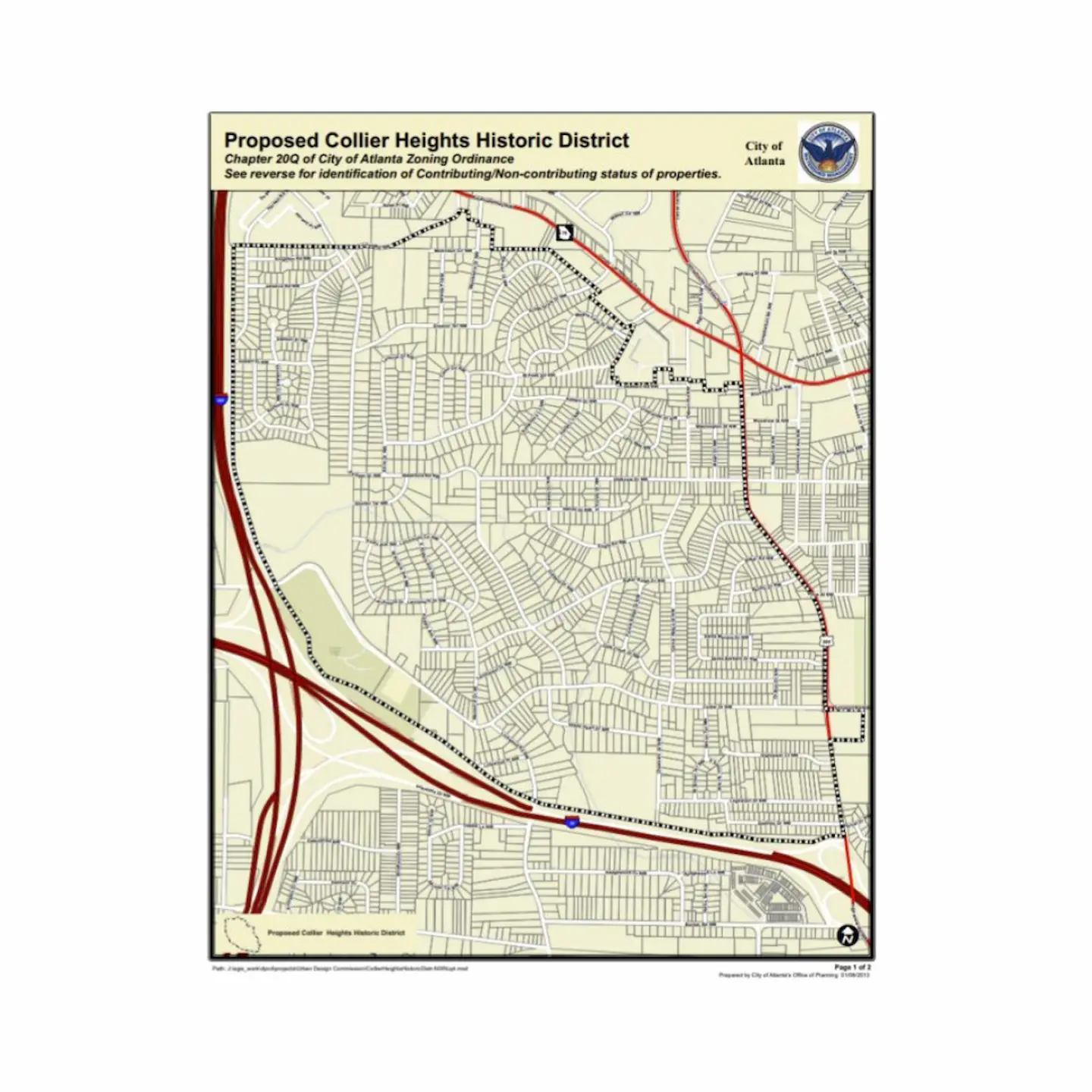

When Walter “Chief” Aiken, Quentin V. Williamson, and John Calhoun helped form the Empire Real Estate Board in 1939 and began buying tracts of land on Atlanta’s westside, they weren’t just investing in property; they were imagining possibilities. Out of that vision rose Collier Heights: one of the country’s first suburban communities built by and for Black homeowners, and now a nationally registered historic district.

While not Atlanta’s first Black neighborhood—that honor belongs to communities like Washington Park—Collier Heights stands apart for its scale, its timing, and above all, its intentionality. This wasn’t a neighborhood solely born from white flight. It was a coordinated effort by Black landowners, developers, and professionals to carve out a space of stability, dignity, and self-determination in the segregated South and a once-divided Atlanta.

What emerged in the beginning was a 177-acre symbol of Black power—both political and economic. Collier Heights became a national emblem of Black middle- and upper-class success, a southern landmark of Black suburban ambition at a time when such ambition defied every barrier.

The neighborhood emerged through grassroots planning and coordinated development after the area was annexed into the City of Atlanta in 1952. A coalition of Black-led organizations, including the West Side Mutual Development Committee and the National Development Corporation, worked with local government and private developers to buy, subdivide, and build housing specifically for African Americans at a time when racial covenants and redlining were still common.

Collier Heights had its highest peak of development from 1941 to 1979, when it became an enclave for Black professionals, clergy, civil rights leaders, and business owners—people like Ralph David Abernathy, Herman J. Russell, and Dr. Asa G. Yancey. By the early 1960s, it had been featured in Time magazine and The New York Times as the premier African American suburban development in the Southeast.

Today, its legacy is threatened.

The rising pressure of gentrification

Rising property values, speculative investors, and short-term rental conversions are colliding with restrictive historic preservation rules. Longtime residents are watching their neighborhood change and wondering whether or not the changes will bring any benefits.

While Collier Heights still offers relative affordability, the community of roughly 1,700 homes across 1,000 acres faces mounting pressures.

The real estate market in the neighborhood is nuanced due to 1) its comparative affordability to the rest of the city neighborhoods and 2) the growing lack of neighborhoods at a lower price point.

“Even folks who've stayed here for years find it harder to save, invest, or pass on wealth.”

Collier Heights had a moderate Black population gain from 2000 to 2010, even while other in-town neighborhoods like West End, Old Fourth Ward, and Summerhill had significant Black population loss, according to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition’s recent report “Displaced By Design.”

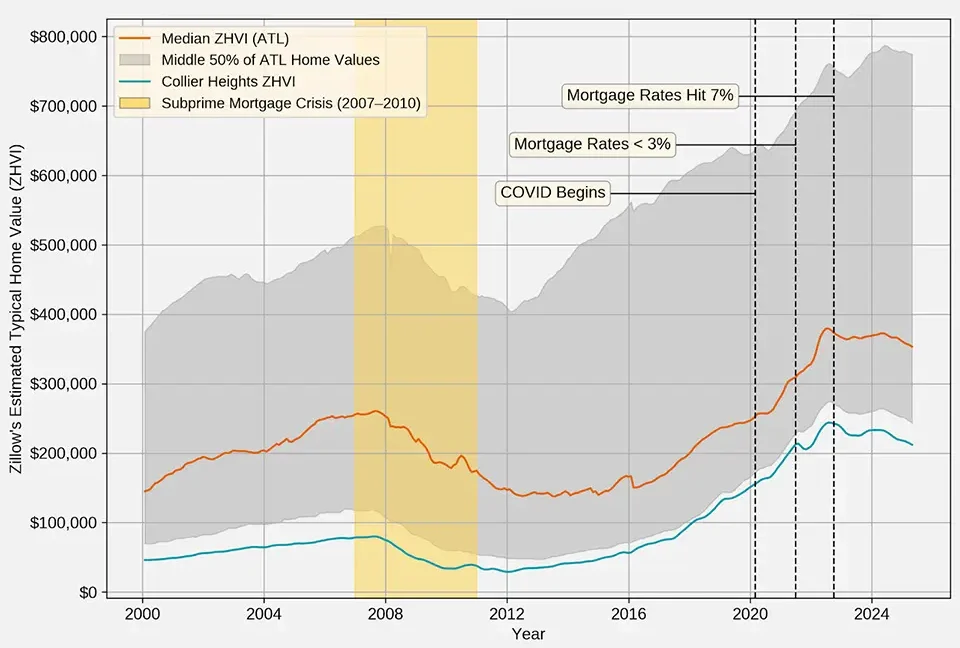

Home Values in Collier Heights Compare to the Rest of Atlanta

(Single-Family Residences)

“As Atlanta as a whole becomes more expensive, everyone—whether it’s investors, developers, or mere mortals looking to buy homes—is looking for comparative affordability,” says data analyst Daniel Krasner. “According to the Zillow Home Value Index, the rest of Atlanta has become more expensive than Collier Heights has at a faster rate. This comparative affordability might put pressure on Collier Heights or similar neighborhoods, especially as neighborhoods at a given price point disappear over time.”

Share of Atlanta Neighborhoods by Price Tier: Single-Family Residences

Between 2014 and 2022, the share of Atlanta neighborhoods with homes under $300,000 dropped from 67 percent to just 37 percent. Simultaneously, those above $600,000 rose from 19 percent to nearly 33 percent. The median home value in Collier Heights remains lower than many parts of the city, but that distinction is shrinking.

The affordability crisis is compounded by stagnant incomes. Between 2010 and 2020, the City of Atlanta’s median income rose by over 42 percent. Collier Heights? Just 2 percent. Adjusted for inflation, the neighborhood’s median income actually declined by 14 percent.

During Canopy Atlanta listening session, a neighbor shared, “Even folks who’ve stayed here for years find it harder to save, invest, or pass on wealth.”

For Collier Heights, this trend puts a spotlight on its position as one of the few neighborhoods still offering relative affordability. But that visibility can be a double-edged sword—attracting interest from investors and buyers priced out of other areas, while potentially accelerating pressures that could price out long-time residents.

“We have fallen in love. It's the greatest drug addiction in the city...Real estate.”

“We have become so hyper focused on greed and maximizing profit that we’ve forgotten the value of the experience of having a good neighbor,” says David Mitchell, executive director of the Atlanta Preservation Center.

Mitchell notes, good neighbors may not keep their houses as up-to-date, but they pick up your mail when you are out of town, check on your pets, come to a graduation, or bring flowers when a family member passes.

In neighborhoods like Collier Heights, the focus on profit has shifted the focus away from working to ensure people can stay in their neighborhoods if they want to, he says.

As more neighborhoods cross into higher price tiers, those like Collier Heights that remain accessible may bear the brunt of a shrinking middle—becoming targets for speculation, displacement, or transformation. It also doesn’t necessarily mean it’s still affordable for those who live there due to the volatility of the housing market in the last five years.

A decrease in median income

While the rise in owner-occupied homes signals positive growth, the affordability challenges faced by some residents remain a concern. The relative income of Collier Heights compared to the broader Atlanta metro area may pose barriers for some potential homeowners. From 2010 to 2020, the City of Atlanta’s median income increased by a net 42.1 percent while Collier Heights increased by only a net 2 percent.

How Median Income Changed in Collier Heights and Atlanta

(Each Year Shown in its Own ACS Inflation-Adjusted Dollars–2010, 2015, 2020)

Even before recent inflation, the cost of living was already rising—and that made small income gains feel smaller. When we adjust for inflation and put everything in today’s dollars, the numbers below tell a different story: Collier Heights’ median income actually went down by about 14 percent over the decade. The City of Atlanta still saw growth, but not as much—about 20 percent up when you account for the changing value of a dollar. Looking at it this way helps show what residents may already be feeling—that a paycheck doesn’t stretch as far as it used to.

How Median Income Changed in Collier Heights and Atlanta

(Adjusted to April 2025 Dollars–2010, 2015, 2020)

Investors see an opportunity

Investors, meanwhile, are circling. Older homes, many with unique architectural features, present ripe opportunities. But renovations don’t always align with historic covenants. And in some cases, investors violate them outright.

The market for investment properties and second homes in Collier Heights presents a more complex picture. Investment activity in Collier Heights is more opportunistic, tied to the age and potential of specific properties rather than broad socioeconomic trends.

Older properties, particularly those with potential for renovation or redevelopment, are attracting investors looking to capitalize on the area’s historical charm and proximity to Atlanta’s urban core. This dynamic suggests that investment decisions are being driven by localized opportunities rather than broad, predictable market forces.

Residents are also frustrated by unequal enforcement of historic rules. “There are houses that really need remodeling, but some of us are told we can’t even add a porch, while new people don’t follow any rules,” one person said. Another shared their experience: “I painted my house and got a citation. They said there were signs, but no one would ever see them.”

Real estate agents have no incentive to tell homebuyers about historic covenants, so they usually don’t, Mitchell says. People are surprised to find out about the regulations after they buy a house and often try to skirt the rules.

“It also comes back to a component of respect,” he adds. “People look at neighborhoods…[to see] ‘Where can I get the greatest return with the smallest investment?'”

The rules themselves are strict. Brick homes can’t be painted. Original or historic chimneys and railings must remain. Even storm doors and awnings must conform to original mid-century designs. And yet, some investors flout these regulations, leaving new owners responsible for costly reversals.

“I’ve seen buyers forced to undo changes just to meet code,” a longtime homeowner said. “It’s not fair.”

These burdens fall hardest on the very people the historic designation aimed to protect. Maintaining an older home, especially one under preservation mandates, can be prohibitively expensive.

Yet there’s no city-funded assistance dedicated specifically for legacy homeowners in Collier Heights, such as exists in historic neighborhoods adjacent to the Beltline. No cushion against increasing taxes or renovation costs.

Increasing short-term rental houses

This localized investment, alongside the increasing appeal and affordability of West Atlanta, is also contributing to the emergence of more short-term rentals in the area, with Collier Heights notably having a higher concentration compared to its neighbors. Data from the city’s Short Term Rental Permit Tracker overlaid with the Atlanta Regional Commission neighborhood statistical unit boundaries reveals that Collier Heights has more short-term rentals than nearby far-west Atlanta neighborhoods.

Short-Term Rental (STR) Permits Issued by Neighborhood Statistical Area (NSA)

Atlanta, GA

The growing presence of short-term rentals in West Atlanta likely reflects investor assumptions that these neighborhoods offer profitable opportunities, especially as more central areas of the city become increasingly expensive and competitive. Collier Heights, for example, may be perceived as relatively affordable and “close enough” to attractions like the Beltline, MARTA, and ease of travel by the nearby interstate. As a result, it may be becoming a spillover zone for those looking to enter the market or capitalize on perceived location value, community history, and historic architecture.

Looking to the future

“I think the idea is to figure out the plan behind how you want your assets,” says Kirsten Daniel, Canopy Fellow and owner of Ateaelle, a business that supports and celebrates Black culture around Atlanta. Her message to Atlantans is clear: “Don’t Sell Ya Grandma House.”

“And so many people work so hard on the front end of their lives,” she adds. “…to build this house, to create this place, this place of love and fellowship amongst their families, of gathering. But they work real hard for that. So it shouldn’t just pass away when people pass. It should be something that is preserved, protected.”

“Don’t Sell Ya Grandma House.”

This sentiment speaks directly to the future of neighborhoods like Collier Heights. The real estate trajectory here will likely depend on balancing an influx of investment with the need to maintain affordability for long-time residents. Future development should prioritize preserving the neighborhood’s character while addressing the diverse housing needs of its community.

As the market continues to evolve, understanding the interplay between owner-occupied trends and opportunistic investment will be crucial.

As Mitchell reminds us, “We have fallen in love. It is the greatest drug addiction in the city… Real estate. It is the biggest drug habit we have. What can I get? Where can I get it?”

Editors: Ann Hill Bond and Mariann Martin

Fact Checker: Ada Wood

Canopy Atlanta Readers: Genia Billingsley and Brent Brewer

I hope this story leaves you inspired by the power of community-focused journalism. Here at Canopy Atlanta, we're driven by a unique mission: to uncover and amplify the voices and stories that often go unheard in traditional newsrooms.

Our nonprofit model allows us to prioritize meaningful journalism that truly serves the needs of our community. We're dedicated to providing you with insightful, thought-provoking stories that shed light on the issues and stories that matter most to neighborhoods across Atlanta.

By supporting our newsroom, you're not just supporting journalism – you're investing in Atlanta. Small and large donations enable us to continue our vital work of uncovering stories in underrepresented communities, stories that deserve to be told and heard.

From Bankhead to South DeKalb to Norcross, I believe in the power of our journalism and the impact it can have on our city.

If you can, please consider supporting us with a small gift today. Your support is vital to continuing our mission.

Floyd Hall, co-founder