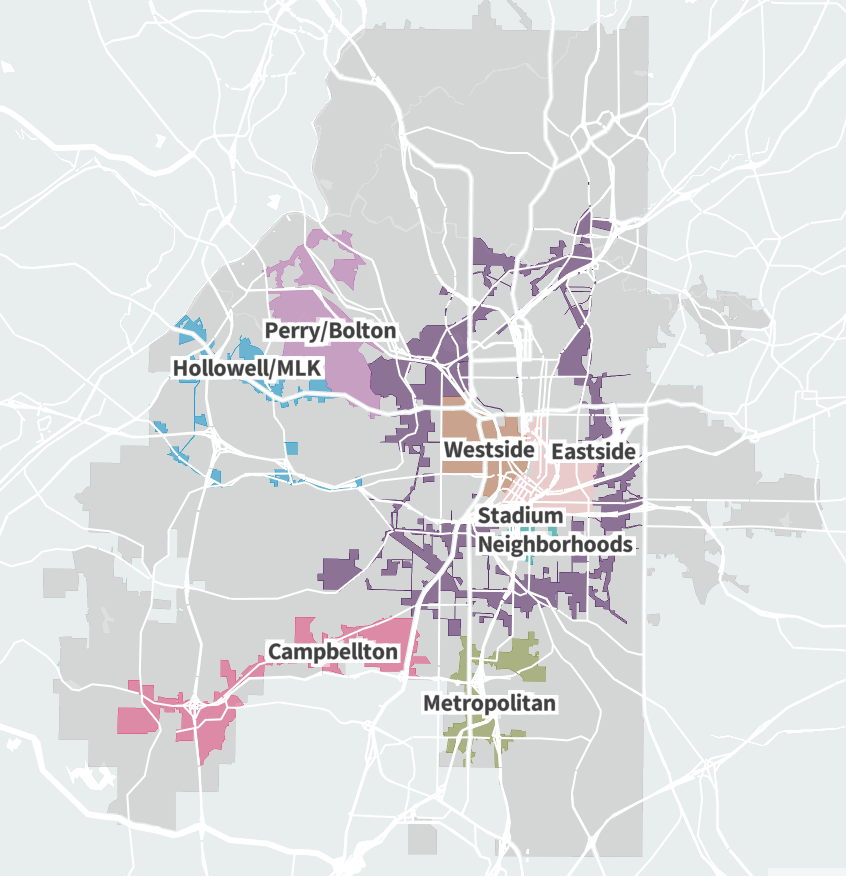

Canopy Atlanta works in neighborhoods to ask community members about the journalism they needed, including Lakewood Heights and adjacent neighborhoods.

Canopy Atlanta also trains and pays community members, our Fellows, to learn reporting skills to better serve their community. Genia Billingsley, the community journalist who wrote this story, is a Canopy Atlanta Fellow.

Last week at a South Atlanta Civic League meeting, the conversation around a recently created mural shifted into a pointed reckoning about history, harm, and accountability.

Neighbors, artists, and local partners gathered to discuss the newly installed mural honoring the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre.

“To me, bottom line, if we did a vote in all historic South Atlanta and that was voted on, that's fine. But we didn't even get a part.”

The National Center for Civil and Human Rights commissioned the mural and worked with Atlanta artist Fabian Williams to create it on the wall of a building owned by Focused Community Strategies (FCS). It was designed to educate the public about one of Atlanta’s darkest chapters. Yet for many residents, the mural seemed to appear without notice or consent. What was meant to bring history to life instead reopened old wounds—revealing how good intentions fall short when community voice is left out of the process.

“Who made the decision for that mural to go in our community?” asked South Atlanta resident Rachel Hall during the meeting. She and her husband’s families have lived in Atlanta since the 1920s, and Atlanta means a lot to them, she said. They chose to live in South Atlanta because of their neighbors, but she doesn’t feel the mural serves the community as it exists today.

“To me, bottom line, if we did a vote in all historic South Atlanta and that was voted on, that’s fine. But we didn’t even get a part.”

Do you live in the South Atlanta area?

Please share your thoughts about the 1906 Race Massacre mural

and the public art process by completing this listening form.

Staff from both FCS and the Center for Civil and Human Rights offered apologies during the meeting, admitting that their outreach process failed to meaningfully involve those who live closest to the mural site and families connected to Brownsville’s past. Their stated intent was to extend truth-telling beyond museum walls. But intent, as several residents reminded them, cannot undo the erasure of lived experience.

The room grew tense when the question surfaced—who approved the final design, and who decided community input was unnecessary?

No clear answer emerged.

Williams described a creative process that went through more than nineteen design iterations. Early versions, he said, depicted aspects of self-defense and community resilience—scenes later removed during the review and approval process. In the meeting last week, it was unclear who made that decision or why those depictions of strength were deemed not the right scenes for the mural.

“My job was to convey how it started and why—and how did it stop,” Williams said.

“It’s a lot to come home to.”

For some residents, the imagery now covering their neighborhood walls feels like a daily reopening of generational trauma.

“It’s a lot to come home to,” one woman said.

But not everyone in the community spoke against the mural. One resident shared that she appreciated the difficulty of telling this part of history.

“I walked over with my son and saw it last week, and to me, it was powerful,” she said. “…So I appreciate this neighborhood—even as gentrifying, because that’s part of life—that there are ways that we can provide historical context about the city and our neighborhood. So thank you for the mural.”

Some families wondered how children would make sense of the mural without historical context. Others stressed that Brownsville’s story—once the name of this neighborhood—is not only about suffering but resistance. In 1906, more than 250 Black men defended their community, helping to end the massacre.

“In terms of work of art. It’s magnificent,” one resident said. “…My issue with it, and this is from what you’re talking about, remembering history. Let’s remember the history correctly. The Riot did not happen. The massacre did not happen here, and the reason it didn’t happen here is because there were black men who were armed, and the only person that was killed was a white deputy. If you look at that mural, you would never know.”

Some ideas of what should happen next were discussed in the meeting, such as adding historical signage, creating companion panels that reflect the full story, and holding listening sessions before any future public art is approved. But no decisions were finalized.

The underlying questions of who is responsible for this process and how accountability will look moving forward remain unanswered.

Editor’s Note: The initial story was updated on Wednesday, October 21, 2025 to clarify that the Center for Civil and Human Rights commissioned the mural, and it is on the wall of a building owned by Focused Community Strategies.

I hope this story leaves you inspired by the power of community-focused journalism. Here at Canopy Atlanta, we're driven by a unique mission: to uncover and amplify the voices and stories that often go unheard in traditional newsrooms.

Our nonprofit model allows us to prioritize meaningful journalism that truly serves the needs of our community. We're dedicated to providing you with insightful, thought-provoking stories that shed light on the issues and stories that matter most to neighborhoods across Atlanta.

By supporting our newsroom, you're not just supporting journalism – you're investing in Atlanta. Small and large donations enable us to continue our vital work of uncovering stories in underrepresented communities, stories that deserve to be told and heard.

From Bankhead to South DeKalb to Norcross, I believe in the power of our journalism and the impact it can have on our city.

If you can, please consider supporting us with a small gift today. Your support is vital to continuing our mission.

Floyd Hall, co-founder